plan

intro

Since it’s release, GPT-3 has gotten a hold of the headlines, sometimes quite literally by writing them. In order to examine what kind of stance GPT-3 takes regarding language, this communication focuses on the interplay between fiction, style and tools, in order to trace a genealogy of the practices and thought which have led to our current state of AI technologies. Indeed, I intend to resituate the currrent wave of interest into artificial intelligence within a tradition of modern computing technologies—a multi-faceted tradition which started with the second-half of the twentieth century, but has deeper roots. The approach here focuses mostly on positions towards thinking, and on ways of doing, manières de faire, in order to highlight three aspects.

First, I want to look at the conceptual environments within which AI practicioners were working, what were the worldviews they were surrounded with, and some of the hypotheses they grounded their work in—that is, their stance towards solving the problem of language processing. Second, I want to show how these approaches translated, and still translate, into concrete, material ways, taking the specific case of programming languages, from LISP and IPL to Python. I’ll finish by examining some of the consequences of this shift from one epistemological style to another, the first one which I will call atomic language, into the second which I will call landscape language. This will sketch out what could be some of the evolutions we might anticipate for contemporary works of fiction, through the lens of a literature of patterns.

The main analytical lens I will adopt here is that of style, not just as a set of aesthetic manifestations, of formal approaches, but style as an epistemological stance. Particularly according to Gilles Gaston-Granger, in his work Essai pour une philosophie du style. What he assumes throughout his work is that specific formal manifestations tend to represent different tendencies and perspectives on a specific conceptual problem. As he analyzes the different ways of doing mathematics, from Euclides to Descartes and vector math, he identifies different ways to highlight concepts such as “scale”, “distance” or “magnitude”. The intertwining of “thought” and “work”, he says, are ways of structuring the world, a task some shared both by works of art, and works of science if we consider style as the expressive function of language.

As the connection between the singular and the collective, style cannot be separated from inspiration. Part of what I would like to show today is also the mutually-reinforcing relationship between the not-so-distant two domains of C.P. Snow. Styles exist across both of those domains, as literary and scientific styles. Fiction and theories aren’t so different from each other (such as the formulas to initiate a suspension of disbelief: Given X…, Once upon a time Y…). We will see how computer scientists and research eras adopt specific styles and themes of scientific fictions in their work, and how this scientific work and their approaches (language as symbol, or language as matter) in turn can influence, more or less directly, writers of fiction.

0 - intro to dartmouth

The first approach to Artificial Research in computer science (even though it was barely called that at the time, the first Computer Science department appearing in 1962), was kickstarted in 1956 at the Dartmouth Summer Reasearch Project on Artifical Intelligence. Organized mainly by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky and Nathaniel Rochester with Claude Shannon signing off on it, it was intended to formalize the diverse approaches which existed at the time, focusing more on what was then called “thinking machines” rather than Artificial Intelligence—the term itself was coined by McCarthy in his proposal. The workshop included 24 final participants, representing what would become two of the main approaches to solving the problem of an artificial intelligence.

The results of the workshop, like so much of AI work at the time, and perhaps still today, vastly underestimated the nature and scale of the task. It did, however, establish AI research as an coherent field, and laid out foundations for two different heuristics for solving the issue of finding, I quote, “how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves”. These two approaches are the formal approach, and the physiological approach. The formal approach, favored by McCarthy, posits in turn that the problem-space, rather than the phenomelogical space should be abstracted away in formally manipulable symbols in order to enable its processing by the computers of the time, computers designed on the assumption of the vast reach of discreete logic operations. The physiological approach, favored by Minsky, intended to re-create the human brain’s plasticity, with the assumption that the simulation of neurons would result in the simulation of thoughts.

These two approaches are two distinct epistemological stances, the former specifically rational, the other specifically phenomenological. Historically, it is the rational approach which prevailed for a time, until the first AI winter of the 1970s and the deep learning renaissance of the late 1990s. For both of these, we can highlight two *fictional environments, the first being taken from logical mathematics, and the second by cybernetics and psychology. I speak of fictional environments as composed of concepts and representative, a worldmaking backdrop, applied techniques of human activity—in particular, notation and tools. Looking at the constitutive criteria of what can make a work of fiction, according to Genette, we find intents, cultural traditions, the reader’s attitude and generic (stylistic) conventions, all things that can shift over time, space and groups of people. Works such as religious texts, political treaties or national epics work as both fiction and non-fiction. And so do the scientific sources and methods we will look at now.

1 - first style - language as symbols

Those participants in the Dartmouth workshop, and their affiliates, are not particularly known for explicitly quoting the works of literary fiction, this connection being sometimes done by critics, commenters and historians through references such as the Golem, wizards, or the Mechanical Turk. The immediate lineage of the first group, headed by John McCarthy, rather, is closer to philosophical traditions rather than artistic ones, and in particular can be traced from Liebniz as rediscovered by Russell to Wittgenstein (whose lectures Alan Turing attended at Cambridge) and Frege. INSERT PROOF WHICH COMES FROM MOST HISTORY OF CS PAPERS. https://archive.org/details/arguingai00samw

1.2 formal notations and characteristica universalis

Looking at the way they consider and depict language,sStylistically, the two elements which stand out here are the symbol and the list, as considered by Leibniz, Russell and finally McCarthy himself as hed devised Lisp.

Starting from his Arte Combinatoria, Leibniz presents Logic as relying on two primary propositions. First, that something either exists, or does not exist source, distant echo of binary processing. The other proposition is that “something exists”, that it is given from outside our logical system. While the latter is a very empirical proposition, almost phenomenological, Leibniz nonetheless needs to integrate these phenomena within his system of logical calculus, and he does so through the process of symbolization; this set of symbols in turn constituted an attempt at his characteristica universalis. The approach here is that of a totalizing process, turning all concepts from the human mind into symbols. Symbols as stylistic and formal representations allowed for the combination of small, similar, primary elements (monads), building blocks for more complex expressions. The consequence of such a symbolization is that, in his words:

If we had it [a characteristica universalis], we should be able to reason in metaphysics and morals in much the same way as in geometry and analysis… If controversies were to arise, there would be no more need of disputation between two philosophers than between two accountants […] Let us calculate.

While Leibniz combines this symbolization process (of events into concept) with his concept the monad, the unary, the singular, his readers, the first of which is Bertrand Russell, depart from this stance. Contemporary predicate logic, while relying heavily on new modes of symbolic notation (such as the Peano-Russell notation), focuses more on relationships between these concepts, rather than on their singularity (e.g. such that A is the C of B doesn’t mean separate things for A and B, but is rather an unit in itself, linking A and B).

This integration of the symbol into relationships of many symbols formally takes place through another stylistic mecanism, the list. Leibniz’s De Arte Combinatoria, Russell’s Principia Mathematica, Frege’s Begriffschrift or Wittgenstein’s Tractacus are all structured in terms of lists and sub-lists, and as such highlight the stylistic pendant to the epistemological approach of related monads. Such a representation shows a particular approach to language: extracting elements from their original, situated existence, and reconnecting ways in very rigorous, strictly-defined ways. As Jack Goody writes in The Domestication of the Savage Mind,

[List-making], it seems to me, is an example of the kind of decontextualization that writing promotes, and one that gives the mind a special kind of lever on ‘reality’.

In this work, Goody examines lists as inventories, early textbooks, administrative documents as public mnemotechnique. The list is a way of taking symbols, pictorial language elements in order to re-assemble them in order to reconstitute the world, the re-assemble it from atoms, following an assumption that the world can always be decomposed into smaller discreete and conceptually coherent units. The list, Goody continues, establish clear-cut boundaries, they are simple, they are abstract and discontinuous. Being based on some singular, symbolical entity, applying logical calculus to lists and their symbols, and doing so in a computing environment, becomes the next step.

2 - putting these ideas into Lisp

This took the form of a programming language, LISP. LISP stands for LISt Processor and, as such, processes lists. It was developed in 1958, the year of the Dartmouth workshop, by its organizator, John McCarthy. It built on some of the ideas of another programming language, IPL (Information-Processing Language), the first geared towards AI. IPL was created by Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw and Herbert A. Simon (who would go on to work a Nobel prize in Economics for his work in that field). IPL’s fundamental construct is also the symbol, which at the time were more or less mapped to physical addresses and cells in the computer’s memory, and not decoupled form hardware.

A link between the ideas exposed in the writing of the mathematical logicians and the actual design and construction of electrical machines activating these ideas, IPL was designed to demonstrate the theorems of Russell’s Principia Mathematica, again an interplay between thinking and doing (which has been shown in the anthropological work of Sennett, Pye, Ingold). ButIPL was used to write a couple of early AI programs, such as the Logic Theorist, the General Problem Solver and some computer chess and checkers programs, all programs which separated the knowledge of the problem (input data) and ways to solve it (internal rules) insofar as the rules are independent to a specific problem. And even though LISP soon displaced it as the go-to language for AI researched, it carried on these ideas.

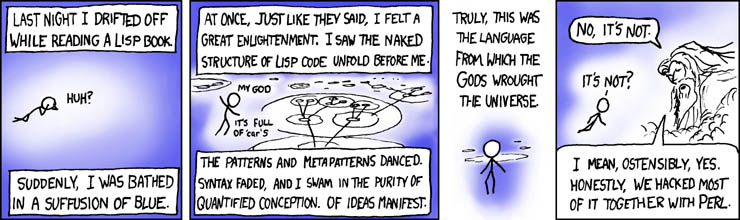

The base structural elements of LISP are not symbols, but lists (of symbols, of lists, of nothing), and they themselves act as symbols (as with the empty list). [http://jmc.stanford.edu/articles/lisp/lisp.pdf] and [http://web.cse.ohio-state.edu/~rountev.1/6341/pdf/Manual.pdf] By manipulating those lists recursively—that it, processing something in terms of itself—Lisp highlights even further this tendency to separate itself from the problem domain, in other terms the real world. Additionally, one of the features of LISP that have stood out the test of time is that it can be defined in terms of itself. This is facilitated by its atomistic and relational structure: in order to solve what it has do, it evaluates each symbol and traverses a tree-structure in order to find a terminal symbol. Such an approach came to be defined as one of the main styles of programming, functional programming, in which value-passing echose the linearity of logical notations (from Russel-Peano to Backus-Naur Form).

```lisp (define (eval exp env) (cond ((self-evaluating? exp) exp) ((quoted? exp) (text-of-quotation exp)) ((variable? exp) (lookup-variable-value exp env)) ((definition? exp) (eval-definition exp env)) ((assignment? exp) (eval-assignment exp env)) ((lambda? exp) (make-procedure exp env)) ((conditional? exp) (eval-cond (clauses exp) env)) ((application? exp) (apply (eval (operator exp) env) (list-of-values (operands exp) env))) (else (error “Unknown expression type – EVAL” exp))))

(define (apply procedure arguments) (cond ((primitive-procedure? procedure (apply-primitive-procedure procedure arguments))) ((compound-procedure? procedure) (eval-sequence (procedure-body procedure) (extend-environment (parameters procedure) arguments (procedure-environment procedure)))) (else (error “Unknown procedure type – APPLY” procedure)))) ```

This sort of procedure is actually quite similar to the approach suggested by Noam Chomsky whe he published his “Syntactic Structures”, where he highlights the tree structure of language, and a heuristic to decompose sentences until the smallest conceptually coherent parts (e.g. Phrase -> Verb-Phrase + Noun Phrase). The style is similar, insofar as it proposes a general ruleset (or the at least the existence of one) in order to construct more complex constructs through simple parts.

Throught its direct manipulation of conceptual units upon which logic operations can be executed, Lisp became the language of AI, an intelligence conceived first and foremost as logical, if not alright algebraic. In terms of applications, the first projects developed in LISP were PhD theses on algorithmic manipulation, using mathematical formulas as highly formalized version of a mathematical expression, with a strong background of a quest for solving artificial intelligence. One of them, Joel Moses’s 1967 doctoral dissertation, supervised by Minsky, co-organizer of the Dartmouth workshop, features the dedication:

To the descendants of the Maharal, who are endeavoring to build a Golem.

This thesis also highlights another tendency of the AI research at the time—an ambiguity towards embodiment. Programs of these early applications are given humanistic names (STUDENT, SOLDIER, DOCTOR, ELIZA, and more dramatically SIN and SAINT) and somewhat anthropomorphized, perhaps trying to match human abilities, rather than side-step it.

The use of LISP as a research tool culminated in the SHRDLU program, a natural language understanding program built in 1968-1970 by Terry Winograd which aimed at tackling the issue of situatedness—AI can understand things abtractly through logical mathematics, but can it do so in a given context? The program had the particularity of functioning with a “blocks world” a highly simplified version of a physical environment, nonetheless made physical. The computer system was expected to take into account the rest of the world and interact in natural language with a human, about this world (Where is the red cube? Pick up the blue ball, etc.). While incredibly impressive at the time, SHDRLU’s success was nonetheless relative. It could only succeed at giving barely acceptable results within highly symbolic environments, devoid of any noise. Writing in 2004, Terry Winograd writes:

There are fundamental gulfs between the way that SHRDLU and its kin operate, and whatever it is that goes on in our brains. I don’t think that current research has made much progress in crossing that gulf, and the relevant science may take decades or more to get to the point where the initial ambitions become realistic.

[http://hci.stanford.edu/winograd/shrdlu/]

Indeed, LISP-based AI was working on what Seymour Papert has called “toy problems”—children’s stories, which were also examined in some research projects, or simple puzzles or games. In these, the world is reduced from its complexity and multi-consequential relationships to a finite, discreete set of concepts and situations. Confronted to the real world—that is, to commercial exploitation—LISP’s model of symbol manipulation, which proved somewhat successful in those controlled scenarios, started to be applied to issues of natural language understanding and generation in broader applications. At first, and despite disappointing reviews from government reports regarding the effectiveness of these AI techniques, commercial applications flourished, such as Lisp Machines, Inc. and Symbolics. Yet, in the 1980s, over-promising and under-delivering of Lisp-based AI applications, which often came from the combinatorial explosion deriving from the list- and tree-based representations., met a dead-end and required a new approach.

2 - mccullough and language as matter

Coming back to the Dartmouth workshop, we can highlight another tradition besides that of logical mathematics, itself with a different stylistic approach. These were a new wave of psychologists and early cyberneticians, represented in the person of Walter McCullough. The tradition from which McCullough comes from is, at the time, dominated by the ideas of Freud, and his understanding of the mind. In his case, the stylistic stance is that of narration and interpretation of narrative events based on literary references, perhaps best seen in his Interpretations of Dreams. In 1930, Freud is awarded the Goethe prize for literary achievements.

In an address to the Chicago Literary Club, titled “The Past of a Delusion”, McCullough thoroughly attacks Freud and his theories in an equally eloquent prose. While he recognizes having similar intents as Freud, understanding the human mind, he accuses his predecessor of having the wrong approach, saying that he established libido as its own “story” and going as far as to say that “his data, method and theory are indissolubly one. Dependence of the data on the theory separates psychoanalysis from all true addresses”. McCullough’s style, in contrast, is more cybernetic, relying on diagrams and input/outputs.

In what is perhaps his most famous paper, “A LOGICAL CALCULUS OF THE IDEAS IMMANENT IN NERVOUS ACTIVITY”, co-written with Walter Pitts, is such an example, in which he connects the systematic and input-output procedures dear to cybernetics with the predicate logic writing style of Russell and others. Prominently featured, in the middle of the paper is a more visual and diagrammatic approach (pic from https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~./epxing/Class/10715/reading/McCulloch.and.Pitts.pdf, and others). Spatializing information in such way, according to Sybille Krámer [https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~sybkram/media/downloads/Epistemology_of_the_line.pdf] has consequences. This attachment to input and output, to their existence in complex, inter-related ways, rather than self-contained propositions, also finds an echo in his critique of Freud:

“In the world of physics, if we are to have any knowledge of that world, there must be nervous impulses in our heads which happen only if the worlds excites our eyes, ears, nose or skin”. (The Past of a Delusion)

This is to be kept in mind when he is recorded as stating, during the Dartmouth conference, that he “believes that the human brain is a Turing machine” (source)—in this sense, it is seen first and foremost as an input/output machine, a reading/writing machine, where the intake devices would play a crucial role. Going further in the processes of the brain, he indeed finds out, in another paper with Letvinn and Pitts, that the organs through which the world excites the brain are themselves agents of process, activating a series of probabilistic techniques, such as noise reduction and softmax, to provide a signal to the brain which isn’t the untouched, unary, symbolical version of the signal input by the external stimuli. (e.g. see McCcullough’s diagrams of logical propositions: [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randolph_diagram] more visual).

INSERT IMAGE HERE https://neuromajor.ucr.edu/courses/WhatTheFrogsEyeTellsTheFrogsBrain.pdf

About the diagram as a notation, Sybille Krämer writes that,

The epistemic rehabilitation of iconicity takes place in the wake of talk of an ‘iconic turn’. This ‘iconic turn’ articulates a call to correct the claim to the absolutism of the linguistic made by the ‘linguistic turn’, as well as to bring to the fore the constitutive contributions of iconicity to our faculty of cognition and to the existence of epistemic objects.

With this turn, then, language is not seen as the vehicle for abstract concepts to be connected to one another, but rather to take into account the specificity of space in our cognitive processes (a two-dimensional spatiality, in the case of the diagram). Along with this spatiality, diagrams tend to imply a reference to something else, an input of some sort, and an output of some sort. As such, the system depicted is always embedded in the world.

The implementation of these ideas was already taking place in the late 1950s, in hardware itself, rather than software, with Frank Rosenblatt’s Perceptron. Another participant in the Dartmouth workshop, Marvin Minsky, while sharing interest in optics and robotics, themselves technologies defined by their interaction with non-intelligent agents, or objects—still, Minsky, like others at the time, thought that the symbolic approach would be more successful than a psychological one. In the endeavour of grasping intelligence, we’ve seen two epistemological stances: either through formal notations, deriving from mathematical logic, or through statistical, diagrammatic, input-output relations, coming from a more biological approach. In the latter approach, it lead to the rise (and not appearance) of the field of machine learning.

4 python and machine learning

Artificial Intelligence today, with GPT-3 as its most recent and impressive manifestation, is no longer written in Lisp, but rather in Python and C++, in what I consider a shift to digital materiality. There are three factors which can explain this new rise in AI, embodying the psychological approach:

- creating probabilistic machine learning classifiers for concepts without worrying about their generality

- creating and using massive infrastructures to combine and mix-n-match machine learning algorithms

- combining the outputs of humans and machines in carefully human supervised ways

We can ascribe to the move from Lisp to Python what he considered being a loss in rigorousness (in defining concepts through symbols), for a gain in effectivity (in letting concepts being exclusively defined in their verbal, contextualized existence within a text). Indeed, most machine learning methods construct hypotheses from data. So (to use a classic example), if a large set of data contains several instances of swans being white and no instances of swans being of other colors, then a machine learning algorithm might make the inference that “all swans are white.” Deductive inferences follow necessarily and logically from their premisses, whereas inductive ones are hypotheses, which are always subject to falsification by additional data. [https://ai.stanford.edu/~nilsson/QAI/qai.pdf] Machine learning is induction with large amounts of data, something Python, in the liberality of its design, fits well.

To what extent does Python match McCullough and the cybernetic approach to intelligence? It does so in several ways. First, it provides an easy interface to a variety of complex datatypes, external sources of information which machine learning models depend heavily on. While Lisp took pride on focusing on a small, abstract set of primitive types, Python allows for complex spatial inputs, called data frames, another echo of Minsky’s frame theory of the mind. Second, Python couples this external input with “under the hood” C++ bindings such as Keras, Torch or Tensorflow, a fast, complex and somewhat lower language than either Python or Lisp. C++ stands as close to the machine as Lisp, but doesn’t bother itself with complex abstractions—it does the job and it is fast, focusing on efficiency and flexibility rather than theoretical soundness. We could interpret this as a similar body-body duality (talking about different parts of the body, like eyes and brains), taking into full account the need for external stimuli, and the need for fast, hardware-like, processing, two things which Lisp did not excel at.

Additionally, Python is not a specific language, in the sense that it doesn’t actually ascribe to a particular style, or paradigm, but is rather what is called a scripting language: it allows for multiple styles, and solves ad hoc situations, in a similar way that Perl is considered a “glue language”. We can also note that GPT-3’s current model is called DaVinci, perhaps implying the Renaissance man’s various expertises.

With OpenAI’s Python implementation of GPT-3, we are no longer considering language as a connected list of atomistic entities, but rather as a continuous, highly-dimensional vector space built from deductive methods. Text is transformed into spatial data, and retrieved as spatial data, before being converted again into a human-readable format for us to read. Instead of assuming a pre-existing abstract structure, a generative grammar, it builds a landscape of all the writings on the web and looks for directions within that landscape.

The Transformer architecture, on which GPT-3 is based, extracts the words from a source document and, in doing so, relates it to every other words in the same document, creating a multidirectional web of relations rather than being restricted to the immediate previous and following words, in a process called attention. We see the diagram here:

Finally, it should be noted that it is scale that makes a difference. GPT-3 is huge, and gets its impressive language generation features from the massive number of parameters it has been trained on (175 billion, two orders of magnitude than its predecessors). Architecturally, it is similar to GPT-2, so its prowess comes essentially from this dataset. It should also be noted that this performance in text generation is well above average, but that its reasoning and explaining skills are well below average, making it far from being a closer candidate to artificial intelligence. It’s good at speaking, but quite bad at understanding.

5 digital matter

5.1 exploring text

Python then allows for text being treated as an incredibly vast landscape, and GPT-3 allows us to navigate that landscape with disconcerting accuracy. A very literal application of this new phenomena can be seen in the game AI Dungeon. Mimicking the classic Colossal Cave Adventure, in which players explore multi-dimensional text-spaces in the 1970s, AI Dungeon allows us to read and write our way through a complex and self-generating maze of places and characters, none of it being ever pre-written by the developers.

And yet, they were pre-written. Not by the developpers, but by all the humans and bots who have written the hundreds of billions of words that compose GPT-3’s training data, and gathered through Common Crawl; there is nothing novel in the output, only in the means of recombining the output. With GPT-3, text is treated as matter, always contiguous, it’s always on the edge of something else, to which it can jump easily and most of the time very coherently.

5.2 some consequences: a literature of patterns

From logical to diagram, from Lisp to Python, human texts are now represented in such a spatial, almost materialistic (if we consider data being a computer’s matter, and indeed training GPT-3 required so much electricity that the bill is conservately estimated at 4.6 of millions of dollars). Since this landscape is constructed from what already exists, it is a snapshot of who we are as a networked, writing species. It finds the patterns in our collective work, and extracts them back to us. David Rokeby considered the computer as a prosthetic organ for philosophy, and I think GPT-3 can be a prosthetic organ for literature. Whatever output it gives us, we still have the agency to accept, reject or adapt it. When asked to write, GPT-3 gives us a literature of slightly look-alikes. a litterature of genres, something Pierre-Carl Langlais has very well exposed in his communication. Turing would probably be amused, because it’s not creating anything, rather it’s imitating everything, without ascribing any particular meaning of aggression, empathy, love or loss, unless specifically told what these are. This equivocal treatment begs the question not of originality, but of what we consider being originality. Similarly to how the ideas and the implementation are connected through hybrids, bridges, in the sense of notational styles, GPT-3 performs under the assumption that all text is connected to other text in complex, continuous ways.

Perhaps we can also answer this in terms of style. Style is the connection between the individual and the collective, how one structures one’s own thoughts and creations to the existing thoughts and creation of other which were, or are, present in the world with us. An individual can stand out so much from the landscape, as a sort of glitch, and performs so well that others integrate it within the common unconscious. The individual becomes a style for others. So perhaps there is nothing truly original or something truly autotelic, whose meaning is absolutely pure. But style, and literature, can set a direction for the rest of the writers, those who blog, tweet, post and comment, as long as it integrates with these other forms of literature.